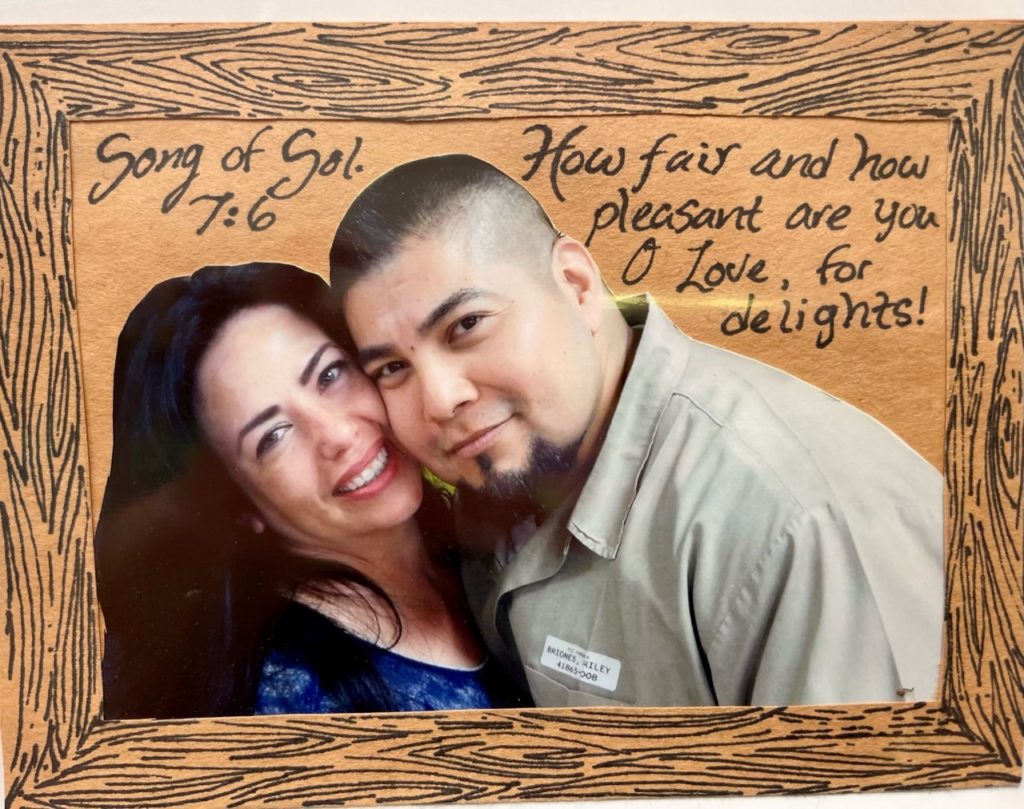

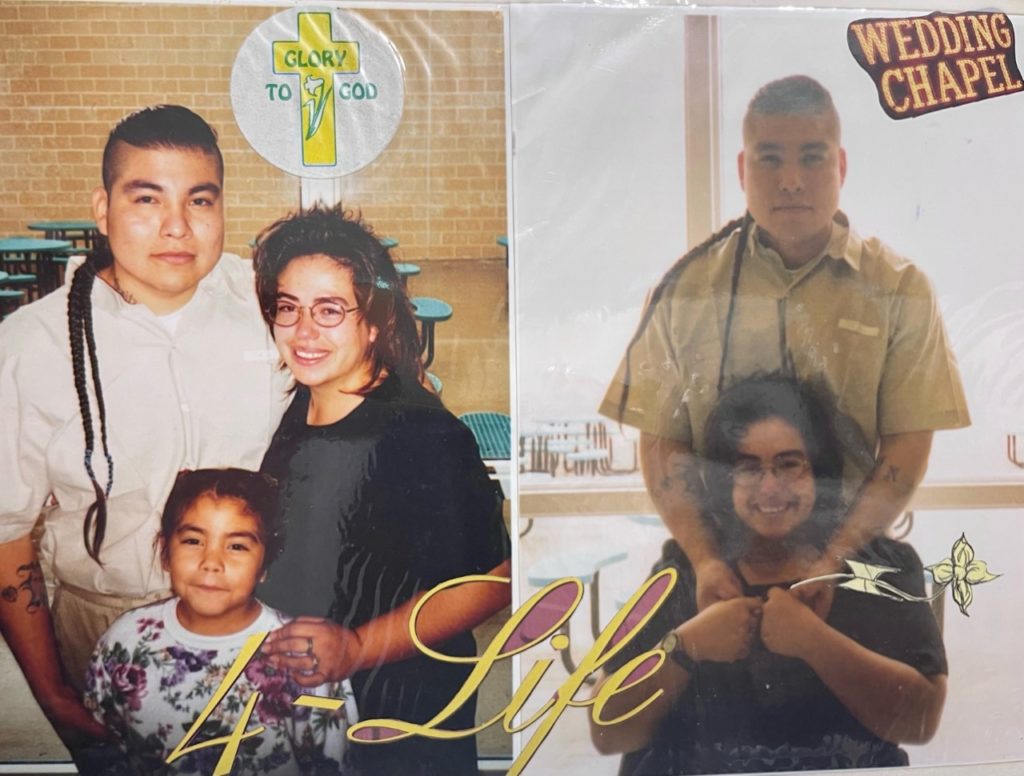

Twenty-five years ago, Riley Briones, Jr., was sentenced to die in prison for a crime he committed as a child. In the decades since, he earned a GED, married the mother of his child, began counseling younger prisoners, and maintained a spotless prison record, without a single writeup, not even for failing to make his bed when he was supposed to. And he did all that even though, as one court put it, his “sentence left no hope that he would ever be released, so the only plausible motivation for his spotless prison record was improvement for improvement’s sake.”

After a series of Supreme Court decisions made clear that the Constitution forbids imposing a life sentence on a juvenile offender unless he is that “rarest of juvenile offenders” whose “crimes reflect permanent incorrigibility,” Mr. Briones had a chance at resentencing. He had reason to be optimistic. The Supreme Court had said life without parole was only allowed for those who were so “irretrievably depraved” that rehabilitation was impossible. At Mr. Briones’s resentencing proceeding, the prosecutor and the judge acknowledged that Mr. Briones had turned his life around:

“I applaud the defendant for his conduct in prison. He’s really doing well in prison.” – Pat Schneider, prosecutor

“All indications are that defendant has improved himself while he’s been in prison.” – Judge Rayes

But the district court still resentenced Mr. Briones to life without parole.

But the district court still resentenced Mr. Briones to life without parole.

The Ninth Circuit, sitting en banc, disagreed. It held that Mr. Briones’s spotless prison record was “precisely the sort of evidence of capacity for change that is key” to determining whether a life sentence is allowed by the Constitution, “yet the record does not show that the district court considered it.” The Ninth Circuit sent the case back down for another sentencing hearing.

But while that sentencing hearing was pending, the federal government asked the Supreme Court to step in. And in 2021, the Supreme Court did just that, requiring the Ninth Circuit to take another look at the case before Mr. Briones could get the sentencing hearing to which he is constitutionally entitled. And three judges of the Ninth Circuit decided that Mr. Briones doesn’t get a resentencing.

Riley Briones, Jr., does not deserve to spend the rest of his life in prison. The MacArthur Justice Center and the law firm of Orrick, Herrington, & Sutcliffe are proud to fight to make sure that Mr. Briones gets a sentence that takes account of the fact that he was a child when he was committed the crime for which he was convicted and of the decades he has committed to turning his life around.

Case Developments

-

March 2022: The Ninth Circuit calls for a response. —

-

February 2022: The MacArthur Justice Center files a petition for rehearing en banc. —

The MacArthur Justice Center files a petition for rehearing en banc, asking the whole Ninth Circuit to weigh in on whether Mr. Briones and others like him who committed their crimes as children can be sentenced to die in prison. A group of more than 50 former prosecutors also wrote a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland calling on the Biden Department of Justice to reevaluate all of the federal juvenile life-without-parole sentences to ensure that only the worst of the worst juvenile offenders will die behind bars.

-

December 2021: A three-judge panel affirms Mr. Briones’s life sentence. —

-

September 2021: The Ninth Circuit hears argument. —

The Ninth Circuit hears argument regarding Mr. Briones’s fate following Jones.

-

May 2021: The United States Supreme Court sends the case back to the Ninth Circuit. —

The United States Supreme Court sends the case back to the Ninth Circuit for another look following its decision in Jones v. Mississippi.

-

July 2019: The Ninth Circuit, sitting en banc, vacates Mr. Briones’s sentence. —

It holds that Mr. Briones’s spotless record during his decades of incarceration show that he is capable of change, particularly because “for the first 15 years of Briones’s incarceration, his LWOP sentence left no hope that he would ever be released, so the only plausible motivation for his spotless prison record was improvement for improvement’s sake.”

-

March 2016: The district court resentences Mr. Briones. —

It acknowledges that “all indications are that defendant has improved himself while he’s been in prison,” but nonetheless resentences him to life.

-

June 2012: The United States Supreme Court issues a decision. —

The United States Supreme Court issues a decision limiting the circumstances in which juvenile offenders can be sentenced to life without parole.

-

December 1995: Riley, Jr., is arrested. —

He is convicted of felony murder and sentenced to life without parole.

-

May 1994: Riley, Jr., drives the getaway car during a robbery of a Subway that tragically ends in murder. —

He is 17 years old.

Key Documents

- Brief in Opposition - 04/06/20

- Appellant's Supplemental Brief - 06/25/21

- U.S. Supplemental Brief on Remand Regarding Jones v. Mississippi - 06/25/21

- Petition for a Writ of Certiorari - 12/2019

- Reply Brief for the Petitioner - 04/2020

- Opinion (U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit) - 07/09/19

- Opinion (U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit) - 05/16/18

- U.S. Response to Petition for Rehearing or Rehearing En Banc - 10/31/18

- Petition for Rehearing En Banc - 07/09/18

- Juvenile Life Without Parole Letter (Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown University Law Center) - 02/17/22

- Petition for Panel Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc - 02/18/22

- Amicus Brief (Federal Public Defender for the District of Arizona) - 03/14/22

- Amicus Brief (Campaign for Fair Sentencing of Youth, et al.) - 03/14/22

For media inquires please contact:

(NOTE: This mailbox is for media inquiries only. All other inquiries, including legal and representation questions, should be submitted through our Contact Form.)