Incommunicado Detention and the Chicago Police Department: Turning the Page on a Human Rights Abuse

Imagine being arrested, taken into custody, your cell phone seized, and no one in your family knows where you are or what’s happened to you. How will you contact your family to make necessary arrangements for your absence? How will you alert them that you need a lawyer to represent you?

Incommunicado detention is an oppressive police practice that occurs when police hold somebody against their will and refuse to let them contact family or a lawyer. People in incommunicado detention are at increased risk of human rights abuses, including being coerced into a false confession or beaten.

In Chicago, the police department has a long history of using incommunicado detention to extract confessions—that includes forcing people to confess to serious crimes for which they’re innocent. Incommunicado detention has led to some of the most notorious CPD abuses, including disappearing people in Homan Square and torture practices committed by former CPD commander Jon Burge.

In Illinois, there has been a law on the books since 1963 that requires police to give people access to a phone call within “a reasonable time” of arrest. There’s also a regulation that says “reasonable” means the phone calls should be given generally in the first hour of arriving at the police station. But this rarely if ever happens in Chicago, because the City says that it doesn’t have to comply with the one-hour requirement.

Instead, CPD arrests people, processes them, interrogates them, puts them in lock-up, and only then gives people access to the phone to call a lawyer or family member — if they do it at all.

Data from the Cook County Public Defender’s office shows that nearly a quarter of all people who appeared in bond court never had access to a phone while detained, and those who were able to make a phone call had to wait over four hours. The statistics are even worse when arrestees are held on suspicious of serious crimes such as murder. CPD arrest data shows that over half of arrestees detained on murder charges didn’t get a single phone call. Those who did get a phone call had to wait an average of 12 hours for it.

As a result, lots of people waive their right to have an attorney present when speaking with police, because they don’t know how to get a lawyer and have to make the monumental decision about whether to speak to police without any advice from a legal representative. Indeed, data shows that just three out of every 1,000 arrestees has access to a lawyer while in CPD custody. Meanwhile, their family might not even know they’ve been arrested, or where they’re being held.

CPD’s refusal to follow the one-hour regulation and their continued denial of phone calls to people in custody is a big part of why Chicago is the false confessions capital of the United States.

What can be done?

The Chicago City Council is considering an ordinance, put forward by Alderperson Leslie Hairston and named “Charles’ Law” after longtime activist and Homan Square survivor Charles Jones III, that would require compliance with the one-hour phone access regulation. The ordinance’s fate is unclear given pushback from the mayor, who prefers a watered-down version of the ordinance, and from CPD. The Illinois legislature also has before it a bill that would fix the troublesome “reasonableness” language that CPD uses to avoid giving arrestees a phone call.

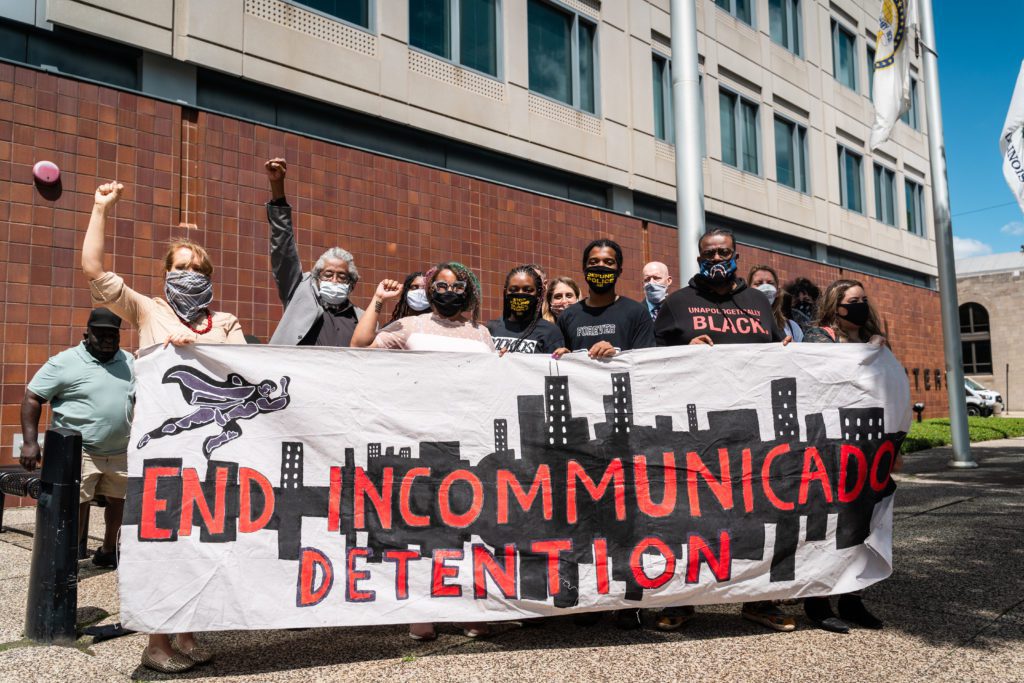

And this summer, as protesters demanding justice in the wake of police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were arrested and held in CPD custody at alarming rates, we filed suit on behalf of a broad coalition of community groups, activists, and attorneys to put a stop to the practice of incommunicado detention. That case is still pending.

We look forward to the day when CPD’s shameful practice of denying phone calls to those in its custody ends, and we no longer hear from clients who provided false confessions to serious crimes after being denied a phone call. Until that day comes, we’ll continue the fight against incommunicado detention in CPD with our partners.

Takeaways

-

Incommunicado detention

is an oppressive police practice that occurs when police hold somebody against their will and refuse to let them contact family or a lawyer. -

People in incommunicado detention

are at increased risk of human rights abuses, including being coerced into a false confession or beaten. -

CPD’s refusal to follow

the one-hour regulation and their continued denial of phone calls to people in custody is a big part of why Chicago is the false confessions capital of the United States. -

The Chicago City Council

is considering an ordinance, put forward by Alderperson Leslie Hairston and named “Charles’ Law” after longtime activist and Homan Square survivor Charles Jones III, that would require compliance with the one-hour phone access regulation. -

The ordinance’s fate is unclear

given pushback from the mayor, who prefers a watered-down version of the ordinance, and from CPD. -

The Illinois legislature

also has before it a bill that would fix the troublesome “reasonableness” language that CPD uses to avoid giving arrestees a phone call.